As expected, Urals broke through the $80 barrier, closing on Friday at $80.21. Brent ended the week at $92, with the US benchmark WTI at $91. This is the closest WTI has been to Brent in some time and likely signals the end of the shale revolution.

Brent has risen by $22 / barrel in the last three months. We last saw such surges in 2008 before the Great Recession and 2011, leading the EU into a brutal, near two-year recession. A replay is likely this time as well, but oil prices need to move significantly higher before the economy craters. The pace of the rise in Brent suggests further increases are likely. Pencil in another $10-20 / barrel in the next, say, 90 days. This would put Brent in the $100-$110 per barrel around year-end.

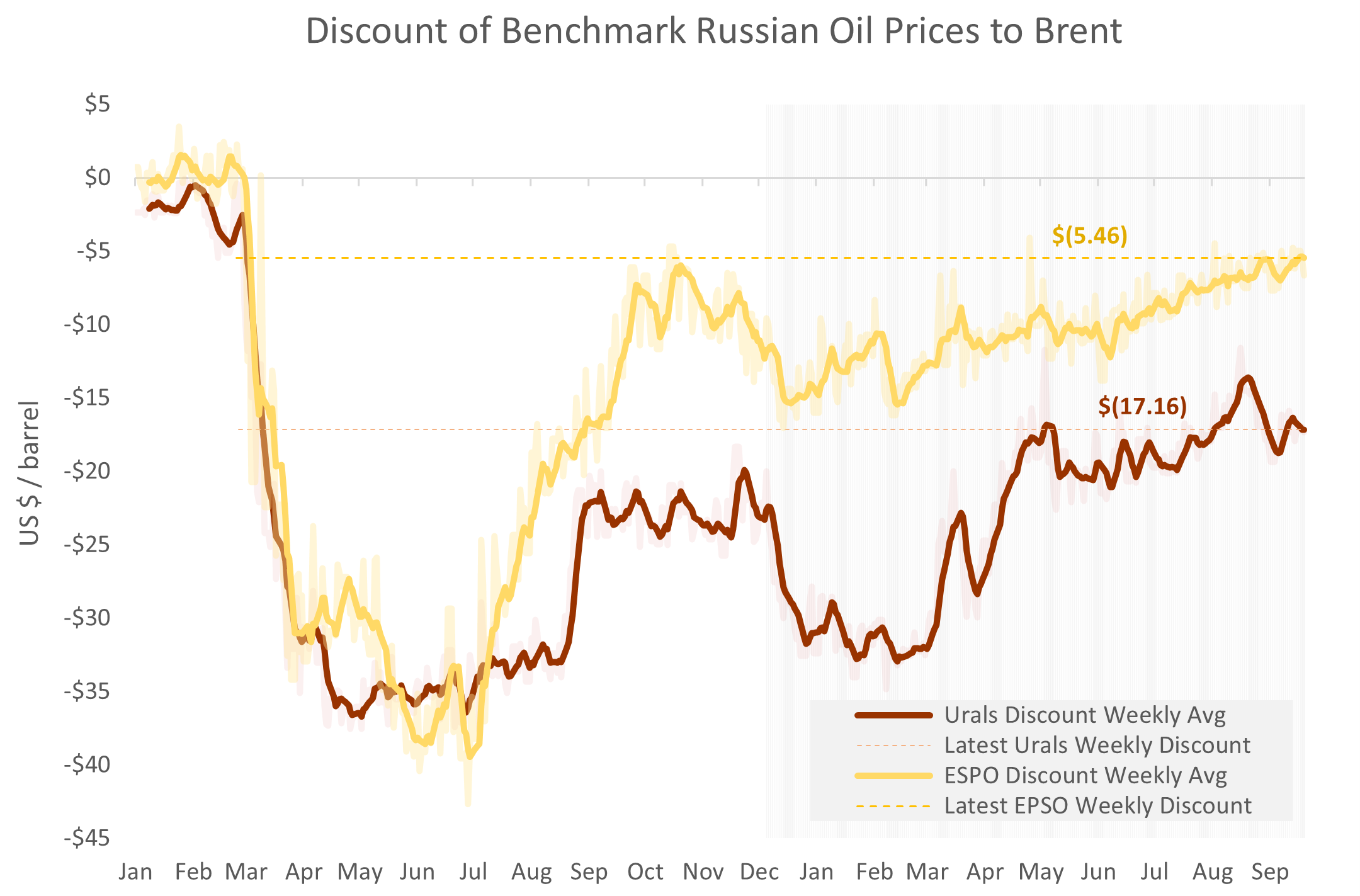

Unsurprisingly, the Urals discount -- the difference between the Urals and Brent oil prices -- compressed last week to just under $14 / barrel, almost the smallest since the start of the war and consistent with the tendency of the spread to contract when Brent is strong. The ESPO discount -- the difference between Russia's Pacific oil price and Brent -- similarly continues to compress, much as we have been forecasting. ESPO is holding around $90 / barrel.

The Urals oil price is near an eight year high and $17 higher than its level year ago, before the implementation of the Price Cap. If we allow Brent at $100 - $110 at year end, that would peg Urals in the $86-$98 range heading into 2024.

Oil and the War

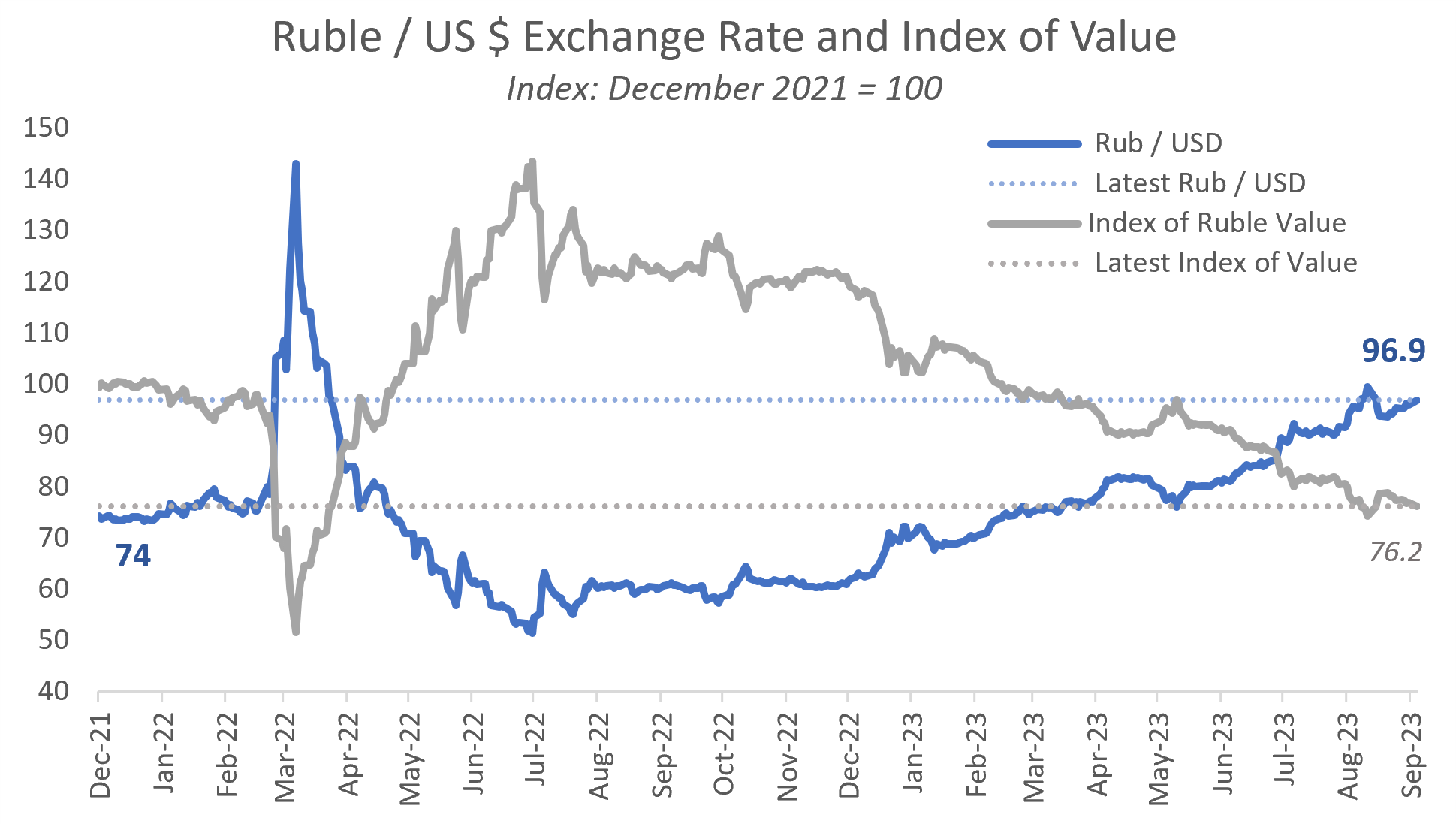

Russia is looking at a massive increase in defense spending. The Moscow Times reports that Russia's Finance Ministry projects defense spending “to jump by over 68% year-on-year to almost 10.8 trillion rubles ($111.15 billion), totaling around 6% of GDP — more than spending allocated for social policy." The Kremlin has limited resources to fund this increase. Tax increases, spending cuts and international borrowing look dicey. Therefore, Moscow is left with the alternatives of bluffing, printing money, or increasing oil revenues. The Russian central bank does not typically bluff. Therefore, Moscow is counting on increasing oil revenues to bankroll the war in Ukraine.

This comes as no surprise for those who follow my macro oil forecasts and is the direct result of a poorly designed and failing Price Cap. For example, in February, I noted in The Oil Supply Outlook (and why it matters for Ukraine) that

The conditions are present for a material tightening of the market in the medium to long term. After 2023, oil price trends favor Russia, and perhaps substantially so. For Ukraine, this could pose a serious threat, as the current European and US sanctions on Russian oil are unsuitable to deal with such an eventuality.

This is belatedly beginning to dawn on the Biden administration. Even two weeks ago, various Biden administration proxies were defending the Price Cap in its current form (Benjamin Harris here and Eric Van Nostrand here). This past week, however, the tone has turned more somber. Bloomberg notes that "Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said that recent market prices for Russian oil suggest that the Group of Seven’s price cap is no longer working as hoped, her first such public acknowledgment of challenges with the program." Some analysts go farther. Julian Lee, Bloomberg's oil markets analyst, in a Washington Post op-ed, It’s Time to Scrap the Russian Oil Price Cap, writes

It gives me no pleasure to say this, but it’s time to scrap the Russian oil price cap.

Lee is a solid, level-headed analyst. But in this case, his advice would be disastrous. I would not be surprised to see Brent hovering around $110 / barrel much of next year. If we allow that every $25 barrel above $55 on a Urals basis allows Russia to double its military spending, then $110 Urals would allow Russia to triple its military budget compared to the pre-war era. This is not only inadvisable, it's absolute insanity.

The reality, unfortunately, is that the Biden administration has not a clue how to fix the Price Cap. None of the administration, Treasury or Fed has the appropriate skill mix, which requires oil markets experience (supply and demand forecasting); oil price forecasting; an understanding of the linkage of oil prices to the economy, politics and society; crude and refined products shipping and pipelines expertise; a solid understanding of black market theory (my unique specialty); and familiarity with the eastern Europe mindset and culture. None of this appears on, for example, the above-mentioned Benjamin Harris's otherwise impressive CV.

The rather unpleasant implication is that Julian Lee's vision, whether de facto or de jure, is likely to be realized: the Price Cap will be scrapped. My Ukrainian readers should contemplate whether this is a desirable outcome, or whether Kyiv might finally wish to take a stand on the matter.

Ukraine's Emerging Funding Challenges

This is even more acute as Ukraine is running up against funding resistance. This comes as no surprise once again, and for more than a year I have been warning about using the US Federal budget as a bottomless piggy bank. To the average American, Ukraine is every bit as exotic and remote as Papua New Guinea, Yemen or Andorra. Why are we spending so much money on that distant place? Is it really our fight? Many, many Americans are asking these questions.

The situation will deteriorate from here. Part of it is simple war fatigue from the funders' side. More importantly, we appear to be heading toward another oil shock, with JP Morgan forecasting a 7 mbpd shortfall in the oil supply by 2030, which is enormous. As oil prices break through $100, $110, or $120, the Russians will feel emboldened and Ukraine's western allies will find themselves enfeebled politically and economically, and they will progressively reduce their exposure to Ukraine. Recent Congressional theatrics and the Slovakian elections can probably be finessed. But they are a clear warning shot and a harbinger of things to come.

The bottom line is this: The Price Cap can and should be appropriately restructured. This would transform the war into a profit center for the US, with about $10 bn in US government annual support to Ukraine offset by about $25 bn in revenues to our defense industry. That would silence Ukraine's critics and ensure Kyiv has plenty of money for both the conflict and reconstruction.