Urals, Russia’s crude oil export price to the west, rebounded this week on a surging Brent oil price. As of Monday, Brent was trading at $89 / barrel and Urals was once again peaking over the $70 threshold, $10 /barrel above the Price Cap.

The Urals discount, the difference between the Urals and Brent oil prices, has widened to more than $18 / barrel. Whether this is as a result of a lag in reporting Urals compared to Brent, or whether it reflects greater difficulty in the Russians placing their exports remains to be seen. At a guess, the Urals discount should trend back into the $15-16 range.

None of this bodes well for either Ukraine or the Price Cap. Barclays Bank sees Brent averaging $92 / barrel in Q4 and $97 / barrel in 2024. Assuming a $15 Urals discount, Urals could average $77 in Q4 and $82 in 2024. As a rule of thumb, each $10 / barrel translates into $25 bn in revenue for the Russian government. Put another way, every $25 / barrel allows the Russian government to double its defense spending compared to pre-war days. Barclays forecast puts Russia's oil price at $21-26 / barrel above its pre-war level.

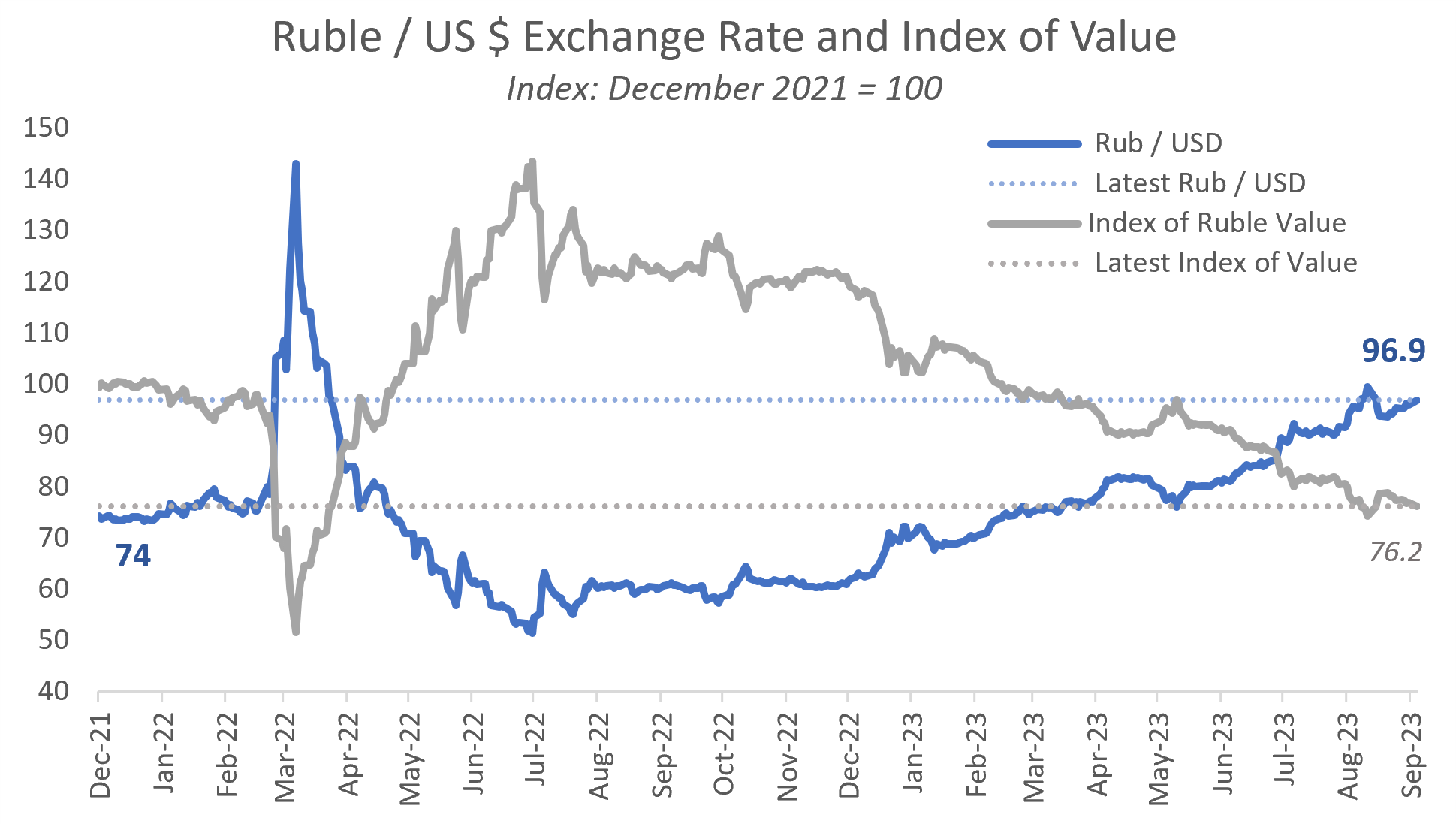

Russia’s Inflation and Exchange Rate

Russia's inflation rate has been much debated. The Russian Central Bank is predicting 6.5% inflation for the year, which is inconsistent with interest rates at 12.5%. At the same time, Steve Hanke of Johns Hopkins has posited an inflation rate of 60%, which is a modeled number and not derived from observed price changes. Inflation is also attributed to devaluation, which vastly overstates the case. The Washington Post notes that "imports still [make] up to 40 percent of the average Russian consumer basket", which creates the impression of some sort of free-wheeling, Hong Kong style economy. In fact, pre-war and pre-covid, imports constituted about 20% of Russia's GDP and are probably substantially less now.

The average Russian mostly consumes Russian goods like meat, dairy, cheese, bread, butter, milk, toilet paper, laundry detergent, and, naturally, vodka, among others. These are almost all produced locally, even if they carry global brands. Imports will be found on store shelves, of course, but in most cases, the Russian consumer can substitute local products for these. Further, Russians spend a large portion of their budgets on items like housing, transportation, and local services like plumbers or haircuts which are non-traded goods. For the average Russian household -- which by definition is not located in Moscow or St. Petersburg -- the day-to-day impact of devaluation is probably on the order of 10-15% of Russians' routine consumption basket. That is, a 20% devaluation translates into perhaps 2-3 percentage points of inflation. This is not enough to move the needle.

Instead, posted increases in the money supply are consistent with observed devaluation and should be driving inflation of similar value. This should manifest as Russians complaining about prices and observed reductions in purchases of routine, Russian-made goods. And it appears to. The above-noted Washington Post articles reports that

One study published Aug. 16 by Russia’s largest market research agency, Romir, found that 19 percent of respondents had begun cutting back on purchases of basic goods such as toothpaste, washing powder and food in July, compared to 16 percent the month before.

These are mostly locally-produced goods, which implies material inflationary pressures domestically, and not only through imports. And this is what we would expect.

Similarly, Russia is seeing spot shortages of gasoline and diesel at filling stations in the country. This results from both devaluation and inflation. Wholesale fuel prices are determined by their value on global markets (in dollars), even as retail gasoline and diesel prices are set administratively and capped. As a result, Russia, one of the world's leading producers of refined products, is seeing a local shortages as refiners find it more profitable to export fuel than sell it on the home markets. Of course, the government is well aware of this. The failure to raise domestic prices is an attempt to suppress underlying inflation and retain public popularity. These initiatives almost always fail, and the government is sooner or later compelled to raise fuel prices.

As I have written before, all this suggests the government is funding the war in part by printing money. The fact that fuel prices have not been raised implies the Kremlin feels constrained in passing through all costs to consumers. In other words, the Kremlin is boxed in politically, allowing ample room for the western powers to revise the Price Cap and Embargo programs. Putin cannot afford to stop exporting oil.