With the situation at the US southwest border deteriorating by the day, policy-makers are looking for causes. On the left, politicians argue that migrants are fleeing violence in their home countries. On the right, analysts contend that US legal rulings and legislation are the cause.

The debate matters, because it influences both who will be held to account and the appropriate policy responses. If the omnibus bill is to blame, then that legislation needs to be fixed, and if the Democrats fail to comply, then they should have every expectation of being held to account by voters.

If, on the other hand, the surge of asylum seekers are motivated by a sudden deterioration in security conditions at home, then US options are fundamentally constrained to building more holding facilities and hiring more Border Patrol personnel and immigration judges. Many of the asylum seekers will be released into the US interior, and their children will show up in some school systems in notable numbers.

Which answer is correct? The data is unambiguous: the February omnibus bill — the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019 — is to blame.

To be clear, the issue is not whether poverty and safety issues exist in the Northern Triangle countries, as well as many other parts of the world. Nor is the issue the legitimate desire of poor peoples for a better life, in this case, in the United States. All these concerns are valid, and have been for a long time. The issue, rather, is whether the massive surge in asylum seeking since last August, and in particular since February, is properly attributed to ‘pull’ factors — the hope for a better life — or ‘push’ factors — the flight from immediate physical threats to the migrants.

It is the pull of the United States.

Here’s the reasoning:

The surge is from multiple countries

When we are speaking of a domestic security crisis, normally it is on the state level. Had the security situation deteriorated over a six month interval, we would expect it to occur in a single country, barring a regional war. In this case, the surge comes from three countries — El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras — all at the same time. There is no common denominator across these countries during the last six months, no shared war or regional disruption. Rather, all three share in common the ability of their citizens to enter the US under US immigration law if they bring a child and claim asylum.

The surge is primarily of families and unaccompanied minors

If countries were experiencing severe domestic crisis, we would expect that all categories of border crossers would increase, notably adults and minors traveling alone, as well as families. However, 84% of the increase has come from persons traveling in family units, and another 6% has come from unaccompanied minors. Families cannot be held and deported before a hearing, and unaccompanied minors can achieve the same effect with undocumented immigrants already in the US. In all, 90% of the increase in border apprehensions in FY 2019, on an annualized basis, compared to FY 2018, has come from the two groups treaty favorably by the omnibus bill.

If the issue were the flight from violence, we would have expected to see the increase across all categories, not only families, but also of adults traveling alone. We don’t see that at all. Instead, the data shows exactly what the experts predicted: unprecedented, lenient treatment of family units and minors would lead to a surge of illegal crossings in this category. This expectation has been fully met.

Northern Triangle security has improved, not deteriorated

As reported by the Seattle Times, the murder rate is El Salvador has fallen by half since 2015 and is now below that of Baltimore City. Allowing that the murder rate stands as a proxy for violence and crime overall, the rate of out-migration from El Salvador should have collapsed, not risen. Instead, border apprehensions of Salvadorans are up 177% over FY 2018 levels. Deteriorating domestic security is not a plausible explanation for the surge.

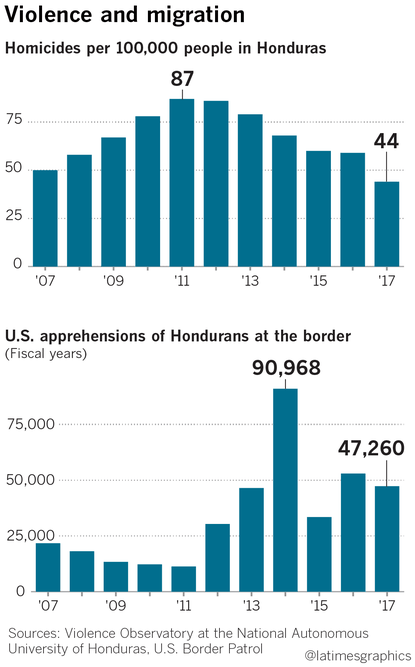

Nor is it the plausible cause in Honduras, where the homicide rate has fallen by half since 2011.

Nor is it true in Guatemala. A study by the Crisis Group reports a 5 percent average annual decrease in murder rates in the Guatemala since 2007, compared with a 1 percent average annual rise among regional peers. As in Honduras, homicides have fallen by half since 2011.

In light of these numbers, an analysis by the Center for Immigration Studies concludes that “the data show no obvious relationship between Central American homicide rates and the number of Central Americans apprehended illegally crossing our border in a year.” This is being too kind. All the available data shows a clear inverse correlation: the surge in asylum seeking has occurred in the context of a sustained drop in homicides rates across all three Northern Triangle countries of El Salvador, Honduras and Guatemala. The argument that violence is driving the surge in asylum seekers is categorically refuted by the available data.

And now they’re coming from all over

A new article from CIS reports that up to 35,000 migrants from more exotic countries like Cameroon, Ghana, the Congo, Haiti, Cuba are making their way through Central America towards the US border. The reports are not yet confirmed through official channels, and the headcount and timing are ultimately uncertain, but that large numbers of asylum seekers are headed towards the US from outside Central America must be taken as highly likely. This was foreseen by Jessica Vaughan, Director of Policy Studies at CIS, who noted at the time of its signing that the omnibus bill “will further expand and institutionalize the catch-and-release policies for those arriving illegally at the border from all over the world.” Again, this speaks not to a security situation in the Central American countries, but rather to a change in US policy which has made it attractive to migrants from all over the world to enter the US illegally at the southwest border with a child and claim asylum.

It’s the economy, stupid

Historically, Mexican and Central American migrants list economic reasons as the primary cause of their interest in moving to the United States.

For example, in an April 2018 survey of public opinion in Honduras (table 91), nearly 83% of respondents listed economic reasons are the cause of a relative’s decision to leave Honduras, as opposed to only 11% who listed violence and security as the primary cause.

The Los Angeles Times documents the situation on the ground in the Honduran city of San Pedro Sula:

In the Rivera Hernandez neighborhood, which has seen significant U.S. investment, homicides have been cut about in half over the last several years, said Danny Pacheco, an evangelical pastor who runs an anti-gang program focused on improving the community’s relationship with police. He said some people leave because violence in Honduras, though reduced, remains too much to bear, [but] he named more mundane factors as bigger drivers of immigration: skyrocketing energy bills, rising food costs and lack of work. “The majority of the population is probably willing to leave if they can,” he said. “And most who can are.”

With respect to Guatemala, press reports list low coffee prices and unemployment, as well as a desire to remit funds to sustain relatives or gather a nest egg to build a house as causes for Guatemalans to move to the US. Our searches show very little on individuals fleeing due to specific threats to their security, although a poor security situation is one factor which encourages emigration. There is no indication in any press report that security has deteriorated to such a fashion in the last year as to warrant a mass migration to the US.

Instead, the Guardian relays a fairly typical story:

Agustín Marcos, 44, used to be an agricultural laborer, but when corn production plummeted, he moved his family to the regional capital, also called Heuhuetenango. Now, he works as a parking attendant, but he still cannot cover rent, food and school fees.

So he is considering migration. “We know people who left just last month and are already in the United States and working,” he said.

Yes, security is poor. But in account after account, Central Americans themselves report the intention to migrate to the US is driven primarily by the desire to work.

The truth is in the market price

Market prices for smugglers are a key metric for enforcement practices at the border. As analysis by others and ourselves suggests, it has become much harder for adults traveling alone to cross the border. “During the Trump administration, the price [for human smuggling] has increased incredibly for those who go alone or who try to cross the desert,” notes Francisco Simon, a researcher on immigration at the University of San Carlos who was quoted in the Guardian. He adds that prices for single adults traveling from Huehuetenango to the US have roughly doubled in the past two years, and are now up to $10,400. But for migrants who surrender themselves at US ports of entry – as most family groups do – there is less risk, and the price drops. Simon’s research has found that in the three departments where most Guatemalan migrants are from – Quiché, Huehuetenango and San Marcos – smugglers’ family rates have halved in recent months.

Such price differentials have nothing to do with local conditions and everything to do with enforcement trends at the US border. The Trump administration’s efforts in shutting down border jumping appear to have born some fruit, but this has been more than offset by the collapse of enforcement against families claiming asylum. When the above-mentioned Agustín Marcos travelled north in 1999 he went alone. This time, he plans to take his 17-year-old daughter. “On my own, they’ll charge me $11,700, but if I go with her, it’s $5,200 for both of us and it’ll be easier to get in,” he said to the Guardian.

Diverging prices for human smuggling make it amply clear that US policy has changed. It has become much harder for individuals to cross, and much easier for families — and only in the past few months, just after the omnibus bill was passed.

The omnibus bill is responsible

Those who contend that the surge in illegal immigration is due to some sudden deterioration in security conditions across three countries will find scant support in the data or anecdote. Rather, every indicator strongly suggests that the surge in illegal immigration is driven by a change in US border enforcement policy, with that change stemming from the passage of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2019 in February. Until enforcement is changed, whether in law or in practice, expect the rate of apprehensions and releases into the US to remain at crisis levels.