Princeton Policy treats illegal immigration as a black market problem resulting from the government attempting to prevent Latin American migrants from selling their labor to US employers. Instead of an enforcement-based policy, we advocate a legalize-and-tax approach to manage illegal immigration. This proven, textbook solution typically reduces black market pathologies by 95% and closes the issue from the political perspective.

In the case of illegal immigration, legalize-and-tax is achieved through a market-based visa (MBV) system, which allows a background-check migrant to enter and work in the US on-demand in return for a market-based fee.

Such a system must meet the needs of three distinct stakeholders:

• Hispanics and Democrats

This stakeholder group is principally interested in gaining status for seven million undocumented Hispanics and assuring better treatment of economic migrants from Latin America. An MBV solution must facilitate status for at least some undocumented immigrants and provide a legal pathway for migrant labor, with an emphasis on reducing predation and victimization associated with the dangerous journey to the United States across Mexico and worker exploitation in the US.

• Fiscal Conservatives

Fiscal conservatives, including organizations like FAIR, care about the fiscal impact of illegal immigration. An MBV solution must improve the fiscal position of the federal government, and lessen the impact on local governments, particularly with respect to fiscal burdens related to education of minors.

• Social Conservatives

Social conservatives are interested in maintaining social cohesion and cultural norms. They place high value on public safety, propriety and accountability and maintaining a political culture which emphasizes tradition and sovereignty. Conservatives typically seek to limit the number of foreigners who reside and work in the country and reduce the abuse of jus soli to obtain legal rights by undocumented immigrants. An MBV solution must demonstrate that it can close the border, end the black market in migrant labor, and limit the migrant headcount while reducing birth tourism and insuring a safe, transparent, and accountable system to handle migrant workers.

An MBV system can meet all of these objectives far better than today’s migrant policy.

From time to time, we explore specific aspects of an MBV system. In this analysis, we focus on one aspect of the migrant issue: the increase in demand for migrant labor resulting from a transition to a legalize-and-tax system.

An Introduction to Black Markets

We treat illegal immigration principally as a black market – and not immigration – problem.

All black markets are artificial and created by governments. They arise as a result of prohibitions or price or wage controls imposed by the government to prevent buyers and sellers of goods or labor from coming together and voluntarily agreeing a price and consummating a transaction.

The most well-known black markets today are in Venezuela, where the government has decreed that a wide range of goods must be sold below cost. This has had the effect of stripping store shelves of stock and creating a black market in goods as mundane as toilet paper. These goods will trade well above their normal market value among individuals in shady transactions – often literally in back street alleys.

A similar effect can be found when minimum wages are set well above their market value. If the difference is large enough – and the $15 minimum wage in New York City probably is, for example – a black market will arise in discounted labor, with workers accepting longer, unreported working hours nominally at the minimum wage, or going off the books entirely and working undocumented for cash.

In the case of the traditional vices – alcohol, gambling, prostitution, marijuana, hard drugs and migrant labor – the prohibition is set with volumes, not prices. In the case of wage and price controls, the manufacture, warehousing, distribution and consumption of a good or service is not illegal. Only transacting at market prices is prohibited. A New York restaurateur can hire an employee and the employee can provide all the services required, just not at a price below the minimum wage floor. Nor is it a crime to possess or manufacture, say, toilet paper in Venezuela. Only its sale at a market value is illegal.

By contrast, volume constraints usually arise because the government believes a given good or service is inherently detrimental. Thus, US government policy seeks to prevent the consumption of heroin or cocaine because policy-makers believe it results from involuntary addiction and is unhealthy for the consumer. Therefore, all of the production, transport, storage, sale and consumption of prohibited items are illegal. Migrant labor falls into this category: an unauthorized immigrant in the US is illegal by definition, as it is to employ or provide certain services to such migrants.

Markets subject to prohibitions or below-market prices will be supply-constrained. Labor or goods will always be in shortage in a supply-constrained market. This means customers who are willing pay above-market rates for goods or services are easy to find. The key to entering the market is a willingness to take risk, break laws and protect one’s turf with force to get supply to market. It is all about supply, whether smuggling drugs over the border or crossing the border illegally in the hopes of find a job.

Supply-constrained markets always involve government force to keep buyers and sellers from willingly coming together to transact for the given good or service. In the case of drugs, this implies drug seizures and arrests of drug dealers and fines and jail times for purchase, possession or usage for drug users.

In the case of migrant labor, the government attempts to prevent sellers of labor from entering the country via border control, including an army of border patrol agents, hundreds of miles of wall, and the agency ICE, tasked with finding migrants and deporting them. Employers are to be formally sanctioned for failing to use E-Verify and employing undocumented labor.

Ending Black Markets

Black markets can be addressed with three different approaches.

• Suppress Supply

As we note above, governments without fail try to suppress black markets by focusing on supply, arresting drug dealers or detaining hotel maids and berry pickers attempting to sneak across the US border. Supply suppression is politically attractive because it externalizes the problem. The problem is the fault of Colombian or Mexican drug dealers or tricky Hondurans enlisting children in fake asylum claims to gain entrance to the US labor market.

Supply suppression has never worked, because enforcement provides the incentive for its own undoing. When supply is suppressed, prices go up, sales opportunities are plentiful and competition is reduced. The effect is much like pressing on a spring. The harder one presses, the greater effort required, the greater the resistance and the more violent the rebound when pressure is released.

Enhanced enforcement increases black market suppliers’ incentive to bring contraband to market. This results in the most extraordinary creativity, certainly in drug smuggling, which has employed ‘mules’ with marijuana-filled backpacks, disposable aircraft, high speed boats, catapults, tunnels, swallowed packets, or drugs canned or hidden in fruits vegetables or manufactured goods – the list is endless.

In the case of migrant labor, options can include walking across the unsecured border; fake papers; tunnels under or ladders over the border; disabling border barriers; fake asylum claims; visa overstays; conveyance hidden in trucks, boats, aircraft; transit over the Canadian border and other means. The very worst, and perhaps the most common, means to circumvent enforcement is bribery, or as the case may be, intimidation and violence. It is the corruption of law enforcement, the bribery of politicians and judiciary, and the intimidation of the press which wreak the greatest damage on society.

Because supply suppression creates the economic incentive for its own undoing, it has virtually no track record of success. True, supply suppression has historically reduced the flow of illicit goods by 10-15%, but this is merely a dent in the business and very far from a meaningful prohibition. Much blood and treasure is spilt for a near meaningless reduction in supply.

• Suppress Demand

Demand suppression is as effective as it is unpopular.

Cold turkey detention of drug addicts vastly reduced addiction rates for hard drugs in Japan and Singapore.

Arizona’s hard line on migrants has also shown notable success. The state brought in tough anti-illegal labor laws in 2007 and reduced their undocumented population by half. Not only that, they have kept the numbers down by closing businesses that use undocumented labor.

Of course, this internalizes the problem. Rather than blaming migrants, enforcement focuses on their US employers. The question is whether such an approach is politically viable.

Nor is it clear that Arizona’s approach achieved its intended goals. On the one hand, Arizona did manage to materially reduce education and health expenditures associated with its undocumented population.

On the other hand, Arizona is the poster boy for unintended consequences with respect to its labor market. When Arizona implemented its tough anti-migrant policies in 2007, Arizona had the 16th best unemployment rate among the states. Today, it is in 45th place. In fact, Arizona has the second worse relative record (change in rank) of all the states since 2007. Moreover, six of the seven states which enacted restrictive laws regarding use of undocumented labor have seen their relative rank, in terms of unemployment rate, deteriorate compared to the other states.

Coercive interventions in markets have a habit of backfiring, and this includes actively preventing businesses from operating by depriving them of employees. Still, demand suppression is a viable option for the conservative purist to the extent the politics are palatable.

• Legalize and Tax

The classic remedy for a black market is to legalize and tax it. The US chose this route with alcohol, gambling and more recently, marijuana. Rather than trying to prohibit a good or service entirely, demand is regulated by a tax regime, with the goods legalized otherwise.

Historically, this approach will eliminate 95% of the criminal pathology associated with prohibition, For migrants, this includes illegal border crossing, murder, rape, kidnapping, human trafficking, theft, corruption, intimidation, smuggling and tax evasion. Domestically, it will materially reduce wage theft, workplace sexual harassment and worker exploitation.

Importantly, legalization does not end all the problems associated with prohibited goods. Alcohol consumption remains the third leading cause of preventable death in the US and is associated with a loss of $250 bn in GDP annually. Nevertheless, the public has accepted these as ‘costs of doing business’. Similarly, the legalization of gambling created much anxiety at the time, but since then, the capital of gambling, Las Vegas, has been transformed into an adult amusement park. Gambling addiction remains a problem for some people, but “what happens in Vegas stays in Vegas” has risen to a selling point, rather than a cry to shutter the city.

Marijuana legalization has – and continues – to cause consternation among politicians, with New Jersey’s attempt to legalize now stalled. And yet, society has not collapsed in those states where marijuana is now legal. Colorado government has prepared a report on its experience at the five year mark for recreational marijuana legalization. (The summary is well worth a read.) There are issues, but far from being a disaster, marijuana legalization has actually improved some statistics (and underscores again that legal alcohol is an order of magnitude more dangerous substance than cannabis).

Migrant workers – primarily interested in mowing lawns or making up the hotel beds in decadent Las Vegas – represent a far lower risk to society than any prohibited drug or traditional vice. Legalization will not make all associated problems go away. Migrants, as the rest of society, will still occasionally commit crimes of various sorts. Notwithstanding, the history of legalization shows that this sort of anti-social behavior will fall to a fraction of its current level.

Moreover, legalization closes the topic as a political issue. Despite the adverse effects of alcohol and gambling, no one is calling for a new prohibition. So it will be with migrant labor. If a well-ordered, fair, transparent and accountable channel for migrant labor is established, and if the government is appropriately compensated for providing labor market access, history shows that illegal immigration will disappear as a political issue of major importance.

Comparing Supply Suppression and Legalize-and-Tax Approaches

As luck would have it, the US is currently running a natural experiment on the unsecured southwest border with Mexico. Three types of contraband are coming over the border: economic migrants, hard drugs and marijuana.

Despite the most aggressive efforts of the Trump administration, both hard drug seizures and border apprehensions have more than doubled compared to the last years of the Obama administration. Not only is a crackdown not slowing traffic, it is actually associated with a doubling of flows!

By contrast, even though recreational marijuana has been legalized in only ten states, marijuana seizures over the unsecured border will have dropped in 2019 by 80% – 80%! – Since President Trump took office. Smuggling is down 95% since its peak in 2009. This is the singular success of the Trump administration at the southwest border, and yet it was not achieved with hardcore enforcement, but through legalization and taxation.

This same effect could be achieved with illegal immigration, with the difference that the border could be closed much more quickly and completely.

The Hispanic Migrant Worker Market Today

If we allow that the migrant market is primarily economic in nature, and as a consequence best treated as a black market, then the transition to a market-based system merits close attention.

We use basic economics and a few concepts to help understand how to think about the liberalization process of migrant labor.

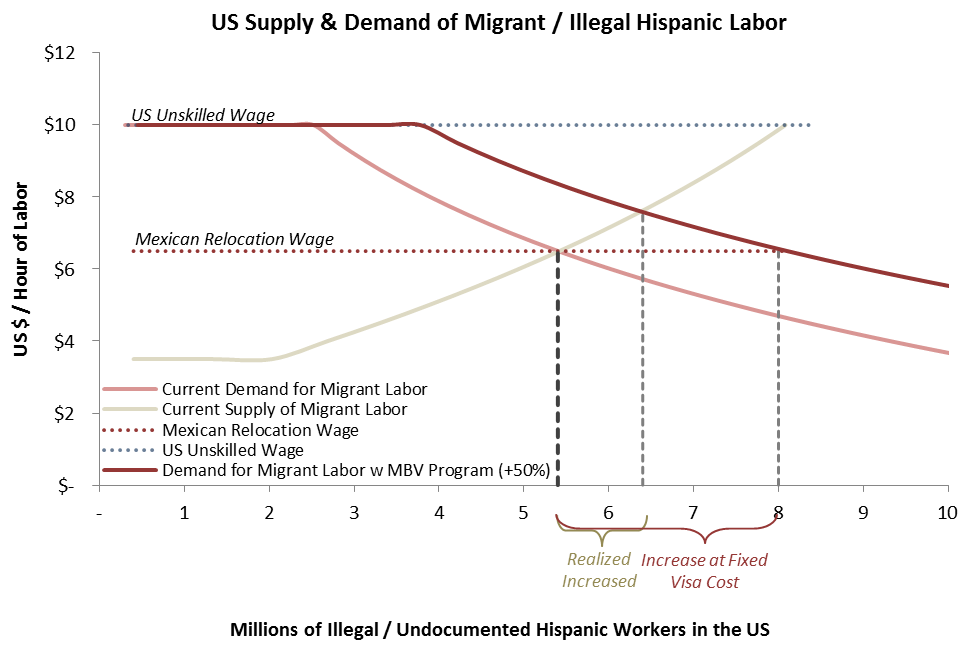

On the graph below, we show the supply and demand for incremental Hispanic, specifically Mexican, migrant labor, based upon our own estimates for supply and demand curves at a medium term horizon of approximately two years.

To this we add two important concepts:

The Relocation Wage

Our analysis suggests that the Mexicans require about $6.50 / hour to induce them to work in the US. This includes

$2.50 / hour to match for unskilled labor rate in Mexico, plus

$2.50 / hour ($500 / month) to offset a higher cost of living in the US, plus

$1.50 / hour as a relocation bonus to compensate them for having to leave their home countries. This would represent their “profit” for coming to the US, a premium of 60% over their home wage.

The total Relocation Wage, as we refer to it, amounts to about $6.50 / hour.

If Mexicans were allowed unlimited entry to the US labor market, then the migrant population would expand until wages in the migrant sector fall to $6.50 / hour, either due to lower wage levels or lower utilization rates (higher unemployment).

The Prevailing US Unskilled Labor Wage

Although Federal minimum wage is $7.25 / hour, not many people are employed at this level. On the other hand, about 20 million Americans work for roughly $10 / hour, and this represents the unskilled wage in the US as we interpret it.

The alternative to a migrant laborer is an unskilled US worker. Given the large number of workers in the unskilled pool, we assume that employers, in a market-based system, are prepared to pay around $10 / hour to migrants.

The Visa Value

Given a Relocation Wage of $6.50 / hour and a prevailing wage of $10 / hour, a Mexican migrant should be willing to pay $3.50 / hour for on-demand access the US unskilled labor market.

Effect of Legalization on Demand

One of the concerns of transitioning to a market-based system is that demand will expand, increasing the inward flow of migrants. Employers, who otherwise would not have considered hiring illegal migrants, would now seek to employ legalized Latin Americans.

Such concerns have always been present when black markets are to be legalized. Because the US has lifted at least three prohibitions historically, the increase in demand can be estimated by reference to experience, in this case, with alcohol and marijuana. US per capita alcohol consumption, for example, declined by 9% from 1915, five years before Prohibition, to 1929, three years before Repeal. Marijuana legalization is associated with an increase of consumption in the range of 5-15%. In Colorado, adult marijuana use increased by 12.5% from 2014, the year after legalization, to 2017. These two precedents suggest legalization would increase demand by 10-15%.

Pew Research’s latest population estimates for 2016 imply approximately 5.4 million undocumented Hispanics in the workforce. Assuming legalization increases demand by the historically observed 10-15%, the migrant worker population could grow 0.5-0.8 million persons over the two years following the implementation of a market-based program.

However, both alcohol and marijuana were legalized with a fixed tax approach. In our proposed MBV system, prices would be actively managed to reduce the incoming headcount and meet conservative goals.

Using a Conservative Objective Function

Conservatives worry about the number of migrants working in the US, as their number is deemed material for issues of safety, social cohesion, and political culture. The attractiveness of an MBV system in part must rest on its promise to restrict migrant and (formerly undocumented) resident Hispanic numbers to materially no more than would have occurred under the next best, viable policy alternative. In this case, the alternative is the current system with 5.4 million undocumented Hispanics (7.2 million including dependents) and an additional 250,000 – 450,000 migrant workers per year.

To achieve conservative goals, we use a price-managed system in which the price of the visa is set by the lowest volume which closes the southwest border and eliminates the black market in resident migrant labor. Rather than setting the volumes directly and administratively – as is the practice today – volumes are set by the price which limits migrant Hispanic numbers to no higher than would have been achieved under the best alternative policy. We deem this a ‘conservative objective function’, as the objective is to restrict migrants numbers to a level consistent with conservative goals while acknowledging that supply suppression does not work for ending black markets, including those in migrant labor.

The graph above illustrates the dynamics. With legalization, demand is 15% higher at any given wage level. In a fixed fee system with a $3.50 / hour visa cost, demand would increase from 5.4 million to 6.2 million workers. With a price-managed system, the value of the visa is allowed to edge up modestly and additional visas are issued with the intent to prevent the re-emergence of a black market in labor. Assuming an unlimited supply of Central American labor at $6.50 / hour, the Hispanic migrant workforce would increase from 5.4 million to 5.75 million and the price of the visa would increase by about $0.30 / hour (+8%). Therefore, in a price-managed system – and assuming our supply and demand curves are approximately valid – the number of visas would increase by 350,000 ceteris paribus. Even with these additions, the Hispanic migrant workforce would only return to the levels of 2011 and remain 500,000 below its 2007 peak.

Both of these numbers should be workable from the perspective of migrants and conservatives alike.

A ‘High Case’ Alternative Scenario for Increased Demand

As a sensitivity test, we can also consider a ‘high case’ scenario in which demand increases by 50% with legalization. With a fixed fee approach, the migrant population would grow by 2.6 million to 8 million Hispanic workers, assuming that an unbounded number of migrants are willing to come to the US at the Relocation Wage of $6.50 / hour.

This outcome would appear to be unlikely, however. We currently count 2 million jobs openings in the migrant category based on our analysis of JOLTS labor market data. Available jobs provide an upper limit on purchases of guest worker visas. Still, assuming a 50% increase in underlying demand due to legalization, the impact could be substantial. But this is easily prevented.

In a price-managed system, the visa price would rise by $1 / hour to $4.50 /hour. Assuming our supply and demand curves are approximately correct, the number of Hispanic migrant workers would increase by 1 million, to 6.4 million, even with the higher price of visas.

A $4.50 / hour visa fee translates into an $11 / hour unskilled wage. That is, 6.4 million migrant Hispanics would be earning more than perhaps 15 million US citizens earning $10 / hour and who are fluent in English and are mostly high school graduates. This outcome would appear to be unlikely. Wages in the much larger indigenous US unskilled labor market probably constitute a cap on wage appreciation for migrant labor. Put another way, US employers are not going to pay more for migrants than they do for US citizens, and this puts a cap on demand for migrant labor in a price-managed system.

As a consequence, we believe 10-15% demand growth is probably closer to reality. Overall, therefore, we might expect liberalization to result in perhaps 350,000 additional visas and an increase in the visa price around $0.30 / hour. Both of these numbers should fall into the respective tolerances of the undocumented Hispanic and conservative communities.

Enforcement

Paradoxically, a seemingly open, price-based system could restrict incremental visa issuance and migrant population increases more than anticipated above.

Illegal immigration today is a strangely asymmetric proposition. Consider the case of the family depicted in the documentary Border Hustle (a must-see video for those interested in understanding the current border crisis). In this story, a Honduran man leaves for the United States with his daughter, whom he is using as a ploy to circumvent US border control.

In the US, the Honduran will likely earn seven times his net wage at home. In the three to five years which will pass before his asylum claim is adjudicated, he will have earned the equivalent of twenty years’ work in Honduras. If he is deported subsequently, he essentially returns to the status quo ex-ante, having earned a substantial nest egg in the meanwhile.

On the other hand, if he chooses to stay as an unauthorized immigrant, he can continue to work with a 3% annual chance of deportation if he lacks a criminal conviction otherwise. He can also expect a solid public school education for his daughter and a well-founded hope that she will become a US citizen in a DACA-style amnesty in the late 2020s.

If he is caught in the future, he will be deported and return to his previous life in Honduras, albeit with some readjustment challenges. He may spend some time in US detention, but probably not too much.

The logic for the economic migrant is all to the upside. The only downsides are in the risks of the journey to the US itself. But otherwise, both migrants’ financial and security situation are likely to improve in the United States, and even if they are ultimately deported, the visit should have proved well worth it.

As a result, the US lacks either a carrot or a stick to deter border crossers. There is not much downside to being caught by Border Patrol and a huge upside in making it into the US interior.

An MBV system changes this calculus. In this world, passing an H-2 visa class background check is sufficient to establish eligibility to work in the US. After that, the key issue is finding a US job that pays well enough to meet personal financial objectives and pay the visa fee. Otherwise, the MBV system is envisioned to allow unrestricted access to the US labor market and rights to all the necessary prerequisites like bank accounts, driver’s licenses and utility and rental agreements.

But this right is not without conditions. Apprehension coming across the desert – now close to a 90% probability – would terminate eligibility for the guest worker program. The loss of access to a market-based visa would therefore become a powerful deterrent. If the migrant labor market in the US is near equilibrium, that is, if there is no great pool of black market work opportunities in the US, then being caught coming across illegally becomes a very expensive proposition indeed. Paradoxically, an open labor market offers much greater potential for border control and restrictions on visa numbers than the current enforcement-based approach.

Demographic Trends

Demographic trends also suggest that legalization of migrant labor should not bring uncontrolled Hispanic migrant population growth.

The undocumented population from the Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras and El Salvador – the four countries anticipated to be first round participants in a market-based program – peaked at 8.25 million in 2007, and has since declined by more than one million, to 7.2 million in 2016.

The Mexican population has taken the brunt of the adjustment, down 1.5 million during that period. The populations of the Northern Triangle countries have grown, but only by perhaps 50,000 per year, according to Pew Research estimates.

On the face of it, therefore, with a visa price filling the gap between the Relocation Wage and the US unskilled wage, the trend data since 2007 suggests no unmanageable surge on the horizon.

This, of course, is not true when the visa price is effectively set to zero, as it is in the case of Northern Triangle residents claiming asylum currently. In such an event, the upper limit on new entrants could approximate the lesser of 4 million – including 2 million adults to fill current job openings and as many dependent children – or the population of the Northern Triangle countries willing to migrate north over the next few years.

Summary

Historically, because supply suppression has been largely ineffectual, whether in drugs, gambling or migrant labor, consumption has fallen by only 10-15% during prohibitions compared to a liberalized system. Therefore, the end of a prohibition does not typically bring a vast surge in consumption, although a medium term increase of 10-15% is well within expectations.

This would imply an increase in the resident migrant population, in a price-managed system, of approximately 350,000 or so with a relatively modest increase in the visa price. With these additions, the Hispanic migrant workforce would return to the levels of 2011 and remain 500,000 below its 2007 peak.